Mastering the Linux command line can be akin to discovering a new world hidden within your computer. It’s a place where text reigns supreme, and a few keystrokes can wield immense power over your system. My personal voyage into this realm began with a Raspberry Pi, a compact yet mighty device that serves as a splendid vessel for learning Linux.

This blog is a friendly guide to help you navigate the basics of the Linux command line, with practical examples tailored for the Raspberry Pi terminal. Whether you’re setting up a server, programming a new project, or just satisfying your curiosity, these commands are your first steps into a broader universe.

Why the Linux command line?

Before diving into the commands, let’s address the elephant in the room: Why bother with the command line in an age of graphical user interfaces (GUIs)? For me, it’s about efficiency and control. Commands can often accomplish tasks in fewer steps than GUIs, and they allow you to perform complex operations by combining simple commands. Plus, understanding the command line deepens your comprehension of how Linux works, which is invaluable for troubleshooting.

Opening the terminal

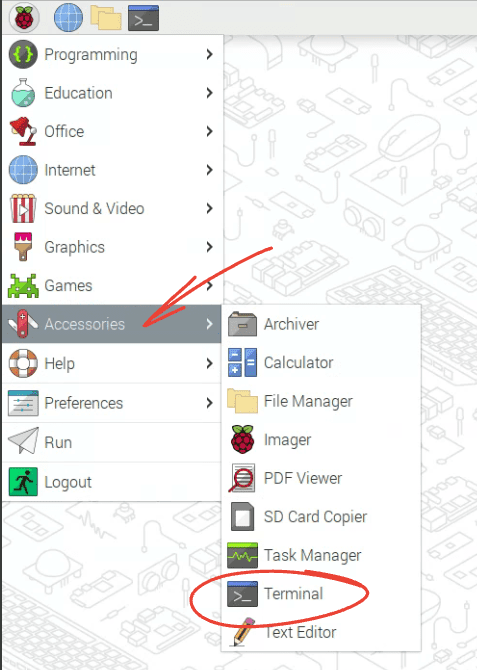

On your Raspberry Pi, the terminal is your gateway to the Linux command line. You can open it via the desktop interface by clicking the terminal icon, often found at the top or in the menu. If, for some reason, you don’t have that icon, you can instead go to “Accessories”> “Terminal”.

Launching Terminal on Raspberry Pi

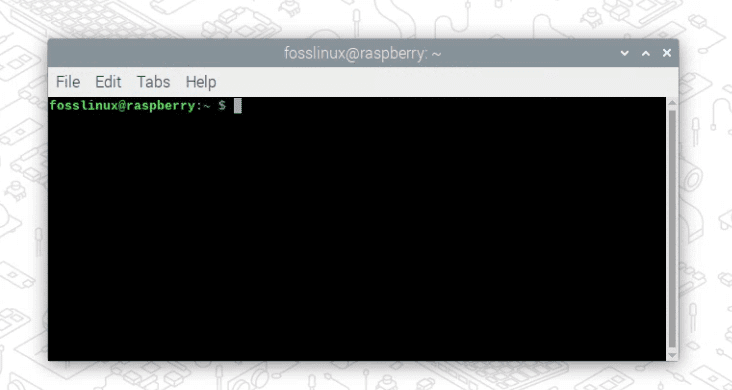

The window that pops up might look unassuming, but it’s your canvas for entering commands.

Raspberry Pi Linux Terminal

Basic navigation

pwd (Print Working Directory)

The pwd command reveals your current location in the file system. Think of it as asking, “Where am I?” in the vast hierarchy of folders (directories) on your system.

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ pwd /home/pi

ls (List)

To see what’s inside the directory you’re in, use ls. It’s like opening a drawer to peek at its contents. I love this command for its simplicity and frequent utility.

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ ls Desktop Documents Downloads Music Pictures Public Templates Videos

cd (Change Directory)

When you need to move to a different directory, cd is your go-to command. Just type cd followed by the directory’s name or path. To go up one level, use cd ...

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ cd Documents pi@raspberrypi:~/Documents $

Working with files and directories

mkdir (Make Directory)

Creating a new folder is as easy as mkdir followed by the name you wish to give the directory. It’s like planting a flag in uncharted territory.

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ mkdir Projects pi@raspberrypi:~ $ ls Desktop Documents Downloads Music Pictures Projects Public Templates Videos

touch

The touch command is your way of creating a new, empty file. It’s akin to laying the foundation stone for a building.

Creating a new file named example.txt within the Projects directory:

pi@raspberrypi:~/Projects $ touch example.txt pi@raspberrypi:~/Projects $ ls example.txt

rm and rmdir

Removing files and directories is handled by rm (for files) and rmdir (for empty directories). Be cautious with these commands; they’re like scissors that can’t distinguish between a mistake and intention.

To delete a file:

pi@raspberrypi:~/Projects $ rm example.txt

To delete an empty directory:

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ rmdir Projects

Example output:

Removing the example.txt file and then the Projects directory:

pi@raspberrypi:~/Projects $ rm example.txt pi@raspberrypi:~/Projects $ cd .. pi@raspberrypi:~ $ rmdir Projects pi@raspberrypi:~ $ ls Desktop Documents Downloads Music Pictures Videos

After removing, the Projects directory no longer appears in the list.

Viewing and editing files

cat (Concatenate)

The cat command displays the content of a file on your screen. It’s like pouring the contents of a bottle out to examine them.

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ cat example.txt This is an example file.

nano

Nano is a user-friendly, text-based editor. Opening or creating a file with nano is like stepping into a minimalist’s office, where you can edit your text in peace.

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ nano example.txt

Managing processes

top

When you want to see what’s currently running on your Raspberry Pi, top is the command for you. It’s like having a dashboard that shows all the moving parts of your machine.

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ top

This output provides a dynamic view of system processes, CPU, and memory usage.

Sample output:

top - 15:29:31 up 1:22, 2 users, load average: 0.01, 0.02, 0.00 Tasks: 117 total, 1 running, 116 sleeping, 0 stopped, 0 zombie %Cpu(s): 3.7 us, 1.0 sy, 0.0 ni, 95.0 id, 0.3 wa, 0.0 hi, 0.0 si, 0.0 st MiB Mem : 926.1 total, 427.6 free, 330.1 used, 168.4 buff/cache MiB Swap: 100.0 total, 100.0 free, 0.0 used. 492.7 avail Mem PID USER PR NI VIRT RES SHR S %CPU %MEM TIME+ COMMAND 1234 pi 20 0 10368 2964 2684 R 6.7 0.3 0:00.07 top ...

kill

If there’s a process that needs to be stopped, kill followed by the process ID (PID) is your command. It’s the emergency stop button of the Linux world.

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ kill [PID]

Example:

To terminate a process, you first need its PID from top or another method. Suppose the PID is 1234:

pi@raspberrypi:~ $ kill 1234

This command doesn’t produce output, but it sends a signal to terminate the process with PID 1234. If successful, the process will no longer appear in the list of running processes when you next run top.

Wrapping up

This guide scratches the surface of what’s possible with the Linux command line, especially on a Raspberry Pi. Each command is a tool in your toolkit, and while some might become favorites, each has its moment to shine. I encourage you to experiment with these commands, explore further, and make this journey your own. The command line might seem daunting at first, but with practice, you’ll find it a powerful ally in your computing adventures. Happy exploring!